Advertisement

The Secret

Resume

Since she was a young child, Julie Lindahl felt burdened by an indefinable guilt, a feeling she could never understand.

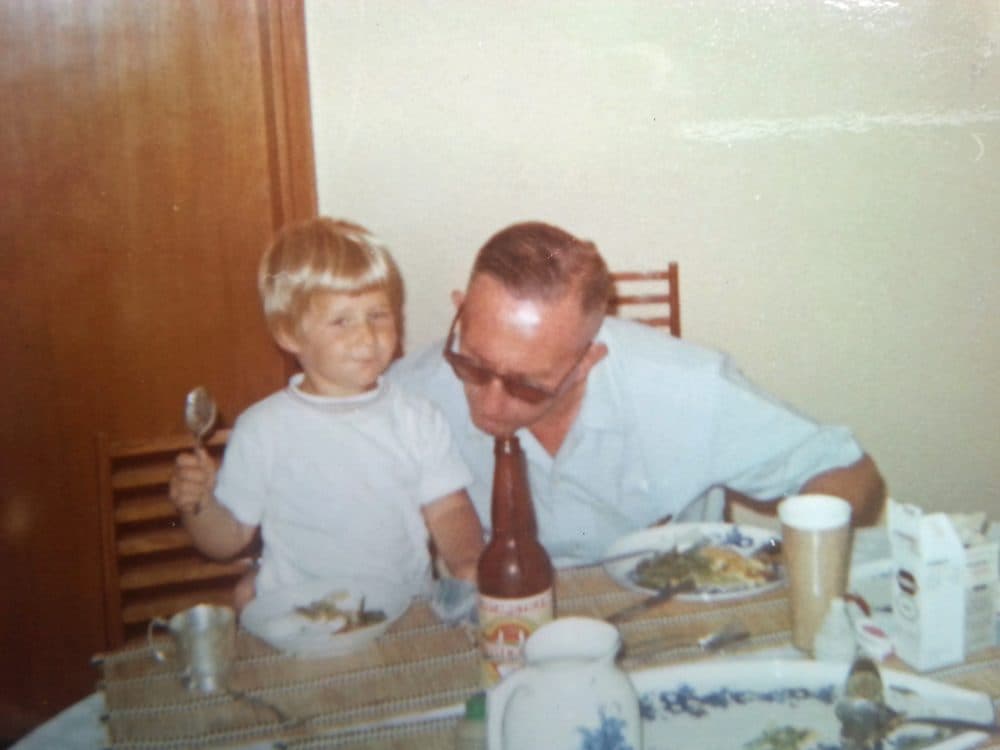

Julie was born in Brazil. Her mother’s German family had moved there in 1960, and she moved a lot while she was growing up. Wherever they were, though, she had an unsettling sense that something was very wrong.

“The feeling that my sister and I always had was that there was this corpse that was lying in the room that was covered over with a blanket, and nobody wanted to uncover it,” Julie says.

As a girl, Julie began to think that that corpse was her grandfather. He had died when she was little, so she barely knew him, but she felt there was something about her grandfather, some secret, that haunted her family.

“Something that none of them felt they could talk about, that they felt so tortured and burdened by,” Julie says, “and they just didn’t know what else to do with it except toss it on the kids.”

Family gatherings were often full of anger, and Julie and her sister escaped whenever they could.

“[My sister] would run into the room next door, shut the door, and get out a face crayon, a black crayon, and paint her face with it, write all kinds of expletives on it, and look at herself in the mirror just to get it out of her system.”

Julie also carried deep, inexplicable shame.

“I had this feeling around me that I had done something so bad that one just couldn't even talk about it,” she says.

Not talking about the corpse in the room weighed on Julie. By the time she was in her 40s, she was struggling with depression. She’d always been an energetic person, but she couldn’t bring herself to get up in the morning. Instead, she’d lie in bed with the curtains closed, unable to stand.

“My husband came to me and said, ‘You know, I think you need to seek help. Do you need to see a psychiatrist, or what do you need?’ And I said, ‘I need to go to the German Federal Archives. That's what I need to do.’”

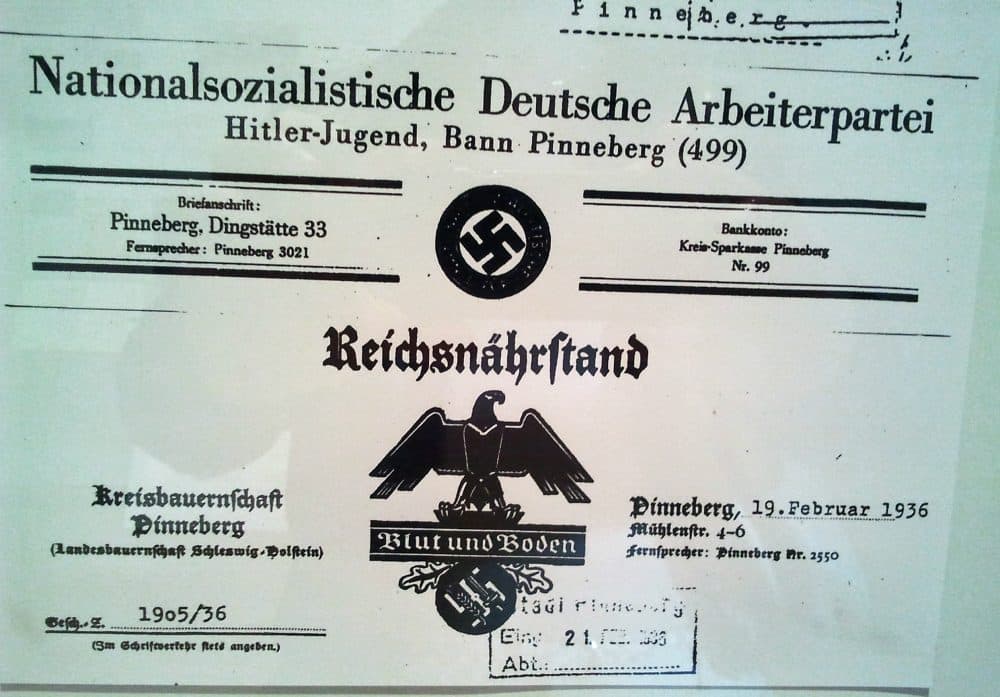

And that’s what she did. Julie got on a plane, and soon she was in Berlin, watching an archivist pull out her grandfather’s records, about 100 pages. They included her grandparents' application to marry as a couple in the SS.

“And I said, ‘What?’" Julie says. "What went through my head was a scream.”

The documents left no doubt that her grandfather had been an SS officer during World War II. He and his wife’s application was thorough.

Julie saw pages of evidence her grandparents had submitted as part of their application to prove their "racial purity": physical examinations, photographs of both of them taken from different angles, family trees. Her own grandmother, a woman whom she loved and who loved her.

“I could see her signature everywhere in these documents, and I remembered all the birthday cards that she'd sent me that had the same handwriting in them,” Julie says. “My grandmother [had] not told me the truth. ... She combined in one personality the great enigma of human beings which is how we can be extremely civilized and terribly barbaric all at the same time."

As far as she could tell, Julie’s grandparents had emigrated to Brazil to flee the accelerating war trials in Europe. Now, Julie felt she needed to dig up everything she could find.

She learned that her grandfather’s job was to oversee farmers in occupied Poland, where he was known for his violent brutality. She wanted to talk with some of those farmers, and one day on a research trip in Poland, she met an archivist named Robert Nowicki, who volunteered to translate.

The next day, Julie and Robert drove for hours through the countryside. They would find three witnesses that day.

The first man was poor and sick. His eyes were angry.

“He'd say something to Robert and stop, and then he would look over at me again and just shoot these furious looks at me,” Julie remembers.

She welcomed the anger.

“To me it felt like, ‘Please, let me take this. Please, just shoot it all at me, just go on, because that's why I'm here.'”

The meeting didn’t last long, but at the end, Julie shook the man’s hand.

She and Robert found the second man carving wood under a tree near his home. He had dementia, but when he heard her grandfather's name, he covered his head with his arms as though he were about to be struck. He started talking as though he were in a flashback — something about being in a barn, about to be shot.

“It was like someone who was being tortured, almost a kind of wailing,” Julie says.

Julie wanted to stop after that, feeling the search was selfish, but Robert convinced her to keep going. So they went to the last house, where a man in his 80s stood in the shade of cherry trees. He had a scar on his face, and he was smiling.

Julie would eventually learn that her grandfather had given him that scar when the man was only about 10-years-old, because he didn’t doff his hat for the officer. His father had been a gardener for Julie’s family, a target of regular beatings from her grandfather.

Julie and the gardener's son talked for hours.

“I had big pools of tears on my face all the time,” Julie says. “There was no other way to be.”

She sensed that it was important to him to share his story.

When it was time to leave, Julie says, “he took my forearms into his hands, and he kind of shook them a bit, and he said, ‘"You didn't do anything, and you need to remember that. It's not your fault.’”

Those words lifted something from Julie, something she’d been carrying for years. Afterward, she went outside to compose herself.

"The man came out with his wife, and [they] placed themselves on either side of me. People who had nothing, who had endured extreme pain, sharing a healing balm with me, just putting a balm on wounds.”

They took her hands, and the three of them looked out silently over the garden he had made, breathing together.

“That was a sort of earthquake experience in life where major things shifted,” Julie says. “What it meant was that I just didn’t have to wander around in that dark space anymore.”

Instead of shame, Julie says, she could now carry responsibility, a responsibility to understand the past and help prevent it from happening again.

“Shame, you can't contribute anything," Julie says, "but responsibility you can do a lot with."

Julie’s work in education and her research into her family’s dark past drain her, but when she feels tired, she thinks of that garden, the shade of the cherry trees and the strangers who held her hand.

This piece is the first part of a series, produced in collaboration with WBUR’s Cognoscenti. Find Part 2 and Part 3 for the full story.

Julie Lindahl's upcoming memoir, "The Pendulum," will be published in September 2018, and is currently available to educators in a shorter version.

An earlier version of this story said that Julie's first discovery of documents included her grandfather's application to join the SS. In fact, at that time she found his application to marry in the SS.

Find Kind World on Facebook or Twitter, or email kindworld@wbur.org to share your story. You can also subscribe to the podcast.

This segment aired on November 21, 2017.