Advertisement

‘It’s Not An Even Playing Field’: How Financial Instability Takes A Toll On Cancer Patients

ResumeThis story is part of our "This Moment In Cancer" series.

Eight-year-old Madison Bergstrom has been battling leukemia for much of her life. While she was living at Boston Children's Hospital for two months of cancer treatment this fall, Madison talked about what she longed for more than anything: her dog Vince, an English mastiff.

"I just want to play with him, and snuggle and love him," Madison said between tears. At the hospital, the little girl could only Facetime with Vince.

Madison has faced more obstacles than most kids her age. At 19 months old, she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL, the most common childhood cancer. Her mother, Shauna McLaughlin, says during the nearly seven years of Madison's treatment, the family has struggled financially.

"Immediately when she was diagnosed I had to stop working," McLaughlin says. "Initially we were in the hospital for about a month and a half. And we had outpatient treatment for the next two years which forbid me to work."

McLaughlin used to work as a dialysis technician. But taking care of her daughter became a full-time job. Madison needed multiple daily medications on different schedules and frequent hospital appointments -- some lasting from 8 in the morning to 5 at night.

"Initially I was with her father, and then we had split up," McLaughlin says. "So because I had to stop working, I went from having two incomes to one, and then one to zero."

How Financial Instability Can Undermine Health

Dr. Kira Bona, Madison's pediatric oncologist at Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, studies how poverty affects health outcomes in children with cancer.

In one study, Bona surveyed families of kids with cancer six months into chemotherapy treatment.

"Families were reporting catastrophic income losses," Bona says. "So just about 1 in 4 families reported that they had lost 40 percent of their annual household income specifically due to treatment-related work disruptions."

Madison has benefited from top-notch cancer care during a time of dramatic advances in research and treatment. In the 1950s, for instance, ALL was almost always fatal. Today, it's curable 90 percent of the time. Still, a growing body of research suggests that a family's financial instability can undermine such advances.

In research published in 2016, Bona looked at data from 575 kids treated for leukemia at leading U.S. cancer centers. She found that even though the kids received the same standard of medical care, the children living in high-poverty areas were more likely to suffer an early relapse compared to kids in low-poverty areas. Specifically, among kids who relapsed, 92 percent of the relapses in high-poverty areas were early relapse — defined as less than 36 months in complete remission — compared to 48 percent in low-poverty areas.

That's important, Bona says, "because it's much more challenging for us as clinicians to successfully cure children who have early relapse than those who have later relapses."

Madison first relapsed in November 2013. (She was not part of Bona's study and hers wasn't technically an early relapse.) When the cancer came back, her mother had to make more heart-wrenching cost calculations. McLaughlin tried to cut down on expenses, but, she says, "having a diagnosis of cancer also incurs lots of new expenses." Additional medical costs, as well as "parking, food outside of the hospital ... lots of gas driving back and forth to Boston, obviously car maintenance is a huge issue."

Once, before taking Madison to the emergency room, McLaughlin had to find a relative to lend her cash for parking.

"It's a low you never felt before. ... Having zero financial stability is debilitating emotionally and physically," McLaughlin says.

Another time, McLaughlin's house went unheated because she couldn't pay the propane bill. A Boston-based nonprofit, Family Reach, helped cover the costs and restore the heat.

"So many people understand the medical toxicity and what cancer treatment has to do to rid the body of disease," says Carla Tardif, Family Reach's CEO. "But there's this whole other financial toxicity that plays a really important role in a patient's chance of beating cancer."

The organization helps families going through cancer treatment cover the cost of basic necessities — from paying the rent and buying food to covering overdue parking tickets and retrieving impounded cars. In addition to the paying the propane bill, Family Reach has helped Shauna and Madison throughout their medical ordeal, including helping with Christmas gifts and arranging for a Zipcar when the family had to go out of town for medical care.

Tardif says most people think of drugs and medical intervention as the most critical part of fighting cancer, but having access to the basics, like food, adequate housing and heat, should also be considered a central part of cancer treatment.

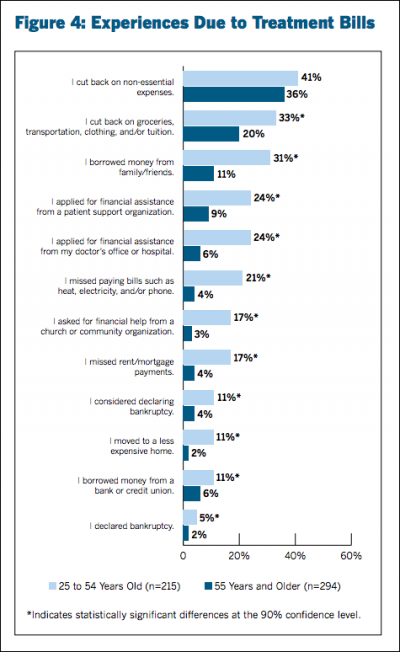

In a survey of more than 500 adult cancer patients nationwide, the 2016 Cancer Care Patient Engagement Report found one-third of respondents age 25 to 54 reported cutting back on food, transportation and/or clothing in order to pay for care. Twenty-one percent reported missing a utility bill, 17 percent missed a rent or mortgage payment.

"The bottom line is, your financial situation affects your chances of beating cancer," Tardif says. "If you have financial resources, you have a better chance of surviving. It's not an even playing field."

Last September, Madison relapsed a second time.

"She was up at night, she was screaming in pain saying, 'My head feels like it's gonna explode,' " McLaughlin recalls.

At the same time, McLaughlin was engaged and expecting a new baby. The family had moved from Whitman to Canton. McLaughlin was juggling a lot. Throughout Madison's long cancer battle, McLaughlin says, she faced a constant balancing act over which bills were crucial and which she could delay. "I was always late on my car payments. I've ruined my credit. I was always stealing from Peter to pay Paul."

How Poverty Affects Health

Bona offers several theories on how poverty may affect health outcomes. Poor children can have worse underlying health, she says, and so could be more vulnerable to the toxic side effects of chemotherapy. And they may have difficulty getting care in a timely manner.

"Perhaps poor children who are at home without a car are not able to get to the emergency department as quickly as they need to, or there may be a delay in bringing them into clinic, for example, if a parent is working multiple jobs and has to get home to get their child," Bona says. Also, she adds, these children may have a harder time sticking to their chemotherapy regimen. She cites one study that found that the risk of a relapse increases fourfold when a child misses just one dose of daily chemotherapy in a two-week course.

"When I care for families who I know are financially struggling, It makes me worried about whether their child may be at risk of having a relapse or having a higher rate of mortality than another child," Bona says.

The whole notion of addressing money issues in the exam room can be fraught, Bona says. But, she adds, it's a problem that the health care system must address as a central part of standard cancer care.

"The bottom line is, your financial situation affects your chances of beating cancer. If you have financial resources, you have a better chance of surviving. It's not an even playing field."

Carla Tardif, CEO of Family Reach

Bona's current research involves surveying families about whether they have sufficient food, adequate housing, heat and other basic resources, and then linking these data to patient outcomes. Bona says it's the first prospective study of poverty in a pediatric cancer clinical trial.

At the same time, Bona and her colleagues across the U.S. are formulating a blueprint for new interventions to help pediatric cancer patients living in poverty. The plan will likely include more systematic screening of children diagnosed with cancer, as as well as novel team partnerships such as having a lawyer embedded with the clinical team, and new collaborations with corporations that address the concrete needs of patients — for instance, Uber to help with transportation to and from the hospital.

Dr. Christoper Lathan, a Dana-Farber oncologist and cancer researcher, says poverty can also undermine the health of adults with the disease.

"If you're poor and living in the U.S. — and we're talking about adults here — you're more likely to get cancer," Lathan says. "Not only are you more likely to get cancers, you're less likely to go to the physician to have your cancer treated. And then, unfortunately, you're more likely to die earlier from your cancer -- just based on income."

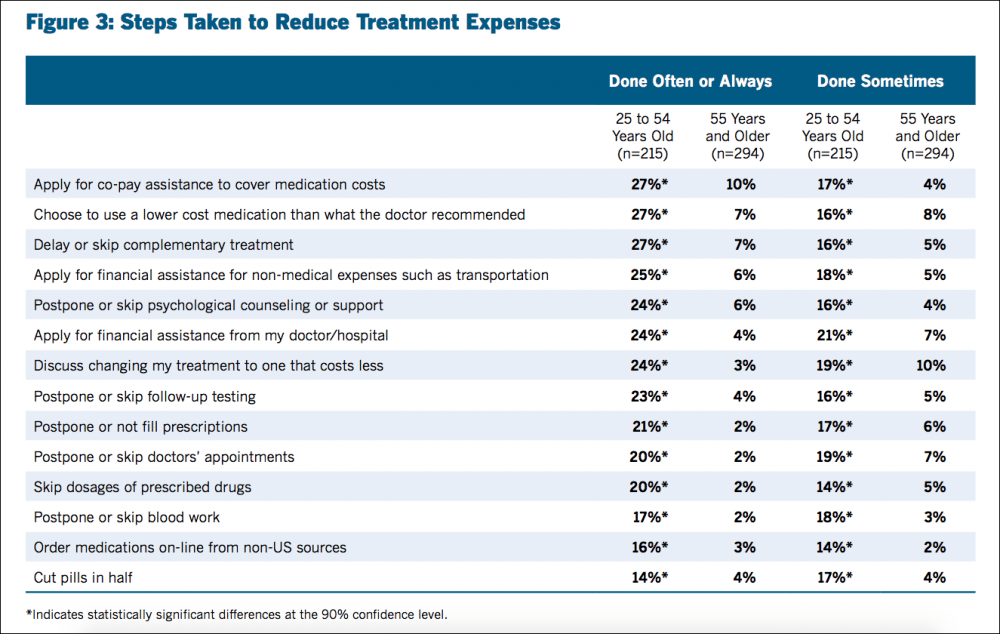

The 2016 Cancer Care Patient Engagement Report found that a large number of patients used one or more "care-altering strategies" to reduce out-of-pocket costs.

Researchers also report that U.S. cancer patients are twice as likely to declare bankruptcy compared to those without cancer. One 2016 study even concluded that "severe financial distress requiring bankruptcy protection after cancer diagnosis appears to be a risk factor for mortality."

"People say, 'cancer makes you poor,' " Lathan notes, but he's also interested in what happens to cancer patients who are already poor when they are first diagnosed. In one study, Lathan looked at 5,000 lung cancer patients and 4,000 colon cancer patients.

"We found that people who were in financial distress at the beginning of their diagnosis were more likely to have more symptom burdens and they were also more likely to have a poorer quality of life," Lathan says. What's more, he adds, is that "the more financial distress you had, the more symptom burden, the more dissatisfaction you had."

The findings are noteworthy, he says, because "it's not just that cancer makes you poor, but if you're poor at the top of the cancer diagnosis, you're generally going to struggle, and that could affect adherence [and] how well you're going to tolerate treatment. And if we don't even ask about that, we are missing an element that could really help patients."

Lathan adds that patients who are well-off, well-educated and who generally feel in control of their lives often fight their disease differently from those who are financially fragile.

"People marshal their forces, their social supports, their financial resources, and they advocate for the care to come at their disease," he says. "For people who are struggling financially ... the cancer is just one of the many problems that they face. So they can't stop their life to fight their cancer."

'A Lot Of Ifs'

Some cancer centers are at the forefront of making patients' financial needs a key component of treatment. At Dana-Farber/Boston Children's, for example, families of every newly diagnosed child are assigned both a social worker and a resource specialist, who can help them connect to myriad services: navigating MassHealth (the state Medicaid program), or getting gift cards for restaurants, groceries and gas. Resource specialists can even arrange to cover a few mortgage or rent payments, as they did recently for a patient's mom, says Joe Chabot, who runs Dana Farber/Boston-Children's pediatric resource center.

Chabot says when he told the woman that her rent would be covered for a while, she was slightly perplexed. "This mother looked at me and she said, 'I'll pay you back?' " Chabot says. "I said, 'No, this is part of your care here.' "

But Dana-Farber/Boston Children's has only four full-time resource specialists for about 500 families, Chabot says, and this can pose challenges.

"There are often resources out there we can connect families with, but we don't because of time," he says. "That's the honest truth."

As for Madison, she just underwent six weeks of treatment in an experimental immunotherapy trial in Philadelphia. In the past few days, we've learned that Madison has tolerated the treatment and her cancer is again in remission. But because this type of therapy is so new and so much about it remains unknown, Madison is far from out of the woods. She will be monitored closely, and might even need a bone marrow transplant. The next few months — and years — will be critical.

"There's a lot of ifs with treatment," says McLaughlin, Madison's mother. "Nothing is a guarantee at this point."

But, she adds, "If it came to any finances, it wouldn't make a difference to me. Because I will do whatever I have to do to make sure that she stays alive."

Do you have a question about cancer research, treatment or care that'd you like us to investigate? Ask it here.

This segment aired on February 2, 2017.