Advertisement

'The Redmen': The History Of McGill's Nickname — And The Fight For Its Removal

Resume

Tomas Jirousek is a member of the Blackfoot Confederacy, a group of Indigenous tribes in western Canada. About 25 percent of his hometown of Whitehorse, Yukon is Indigenous. But when Jirousek first arrived at McGill University in the fall of 2016, he was one of only about 150 Indigenous students out of nearly 28,000 undergrads.

"There were these pockets where I saw myself reflected," Jirousek says. "But it almost felt more isolating, now that I think about it, to know that the only spaces where you are really reflected are, you know, the First Peoples' House, the Indigenous studies program, within the few Indigenous student groups that we have. I had never really felt as othered as I did here at McGill."

But before long, Jirousek found another place he fit in: the varsity crew team.

"It was amazing," he says. "Like an instant family, almost. I was just so lucky. To get to travel around Eastern Canada with some of your best friends."

McGill's Team Name

Varsity sports at McGill and other Canadian universities aren’t as high profile as they are in the U.S. Mascots and team nicknames aren’t emblazoned on every piece of gear. So it wasn’t until later that fall that Jirousek first came in contact with McGill’s nickname: The Redmen.

"I went to a football game, and that's when I first heard it chanted," he says.

Jirousek says he had heard “Redmen” used as a slur growing up. He was shocked to hear it on his college campus.

“I had never really felt as othered as I did here at McGill.”

Tomas Jirousek, McGill varsity athlete and Undergraduate Indigenous Affairs Commissioner

"I had this reaction — this visceral reaction," he says. "And it just struck me as so archaic — so outside the image that McGill was trying to project or the institution that McGill was trying to be."

Jirousek began learning more about the history of the Redmen name and its place in campus culture.

"Seeing old pictures of jerseys and helmets and just listening to the stories of some of the older Indigenous students, alumni and professors, it was just heart-wrenching," he says. "A lot of Indigenous students just didn’t feel comfortable in McGill Athletics because of the Redmen name."

McGill history professor Suzanne Morton says that when McGill started fielding varsity athletic teams in the late 1800s, they had a lot of different nicknames. They all paid tribute to James McGill’s Scottish heritage. And … his hair.

"The Red team, the Red and White team, sometimes the Red Pucksters," Morton says. "Sport-specific names — the Red Cagers ..."

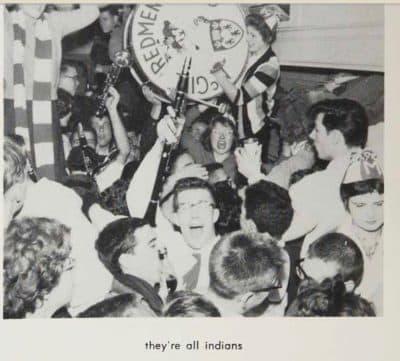

The Redmen entered the mix in 1927, and it was first accompanied by Native imagery in the 1940s.

"There's a new football coach hired from the United States, and he wants to make football more spectacle," Morton says. "He wants crowds. And so we have the input of really explicit Indigenous images onto, particularly, the football team.

"You have images of fierceness, bravery, savagery. The marching band, all of a sudden, has a cartoon of an Indigenous man in a McGill uniform — braids flying, carrying a football. You get new songs which talk horribly about things like scalping and warpath."

New nicknames entered the mix as well: for a while, men’s teams were called the “Indians.” From 1961 until 1976, women’s teams were called the “Super Squaws.” And while all this was happening, there were hardly any Indigenous students on campus to speak up against racism.

The Indian Act

And here’s where some background in Canadian history becomes really important. In 1876, the Canadian government passed a statute called the Indian Act. One of the many things the Indian Act did was define "status": who was Indian and who wasn’t. And only people with status were allowed to enter Indian reserves.

The Indian Act also ruled that any Indigenous person who enrolled in a Canadian university would automatically lose their Indian status. And without status, these students would never be allowed to return home.

Suzanne Morton says that through her research, she’s identified just two Indigenous students who graduated from McGill between 1900 and 1918. And in the 40 years after that, she hasn’t found a single one. Pop culture stereotypes were the only exposure most McGill students had to indigeneity.

"They see Indigenous people in the movies," Morton says. "They may seem them on TV with Daniel Boone in the 1950s. But there’s no contact with actual people."

Morton says more Indigenous people started attending McGill when the Indian Act was amended in the early ’60s. But even into the late ’80s, Native students made up a tiny part of McGill’s student body.

"I'm not sure the university even kept reliable statistics in that regard," says Ned Blackhawk, a professor of American Indian history at Yale University and a member of the Te-Moak tribe of Western Shoshone Indians of Nevada. "Less than one percent of one percent is probably the closest number."

In the late ’80s, Blackhawk was an undergrad at McGill. And in his second year, he walked onto the varsity track and field team.

"It meant that I was in the gym a lot," he says. "And there was a giant Redmen logo above the scoreboard, or right alongside it, that was probably the size of a fairly large urban billboard.

"Basically, it had the side portrait visage of an angry Indian man with a protruding nose and headdress, under which it just said 'Redmen.' So it was something that I really couldn’t avoid. And I didn’t, at the time, have the vocabulary or set of intellectual commitments to really call into question that image. But it was something that bothered me and something I had to confront."

In 1991, Blackhawk and a fellow undergrad led a campaign to change the Redmen name and remove the Native imagery that came with it.

"We wrote opinion editorials for the McGill daily newspaper," Blackhawk says. "We were interviewed on the McGill university radio station. We held teach-ins. We were, just, basically involved in sets of consciousness-raising efforts."

And in March of 1992, McGill’s Athletics Board decided to get rid of the Redmen logo.

The billboard-sized Indian head in the gym went away. The football and hockey helmets were changed to sport the McGill crest. But the Redmen name stayed.

In a press release, the chair of the athletics board expressed his belief that getting rid of offensive imagery was enough to disassociate the name from its derogatory connotation. Ned Blackhawk and other Indigenous students felt differently.

"Seeing that image taken down or removed over time — seeing these things dropped from the hockey team or the football helmets — did bring me a sense of satisfaction," Blackhawk says. "Though, I wish they had come up with a different name."

Reconciliation

In recent decades, Canadians have faced their country’s history of Native oppression and its lasting consequences. And in 2015, the Canadian government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission underscored the importance of education in creating a more just society for Indigenous peoples and culture.

The McGill Provost’s office formed a task force on Indigenous Studies and Education shortly after. When it published its 52 calls to action in 2017, replacing the Redmen name made the list.

But a year went by. Tomas Jirousek was finishing up his sophomore season on the crew team, and he says it didn’t seem like McGill was taking any real steps towards change. So he and some other students decided to take action.

"Out of Indigenous student activists here at McGill, I was the only athlete at the time," Jirousek says. "With me being a varsity athlete, I felt that it was something I could really push."

Jirousek spoke to news outlets and moderated panel discussions with Indigenous experts. He started speaking to fellow athletes — the students most closely tied to the school nickname — and explained that the name has the same impact on Native students that other racial slurs have on other groups.

"A surprising number of athletes have never really thought about the history of the name or how it impacts us as Indigenous people," Jirousek says. "But once I think a lot of athletes face the kind of the damage that the Redmen name has done, it makes it click quite a bit easier."

In October, Jirousek did something that Ned Blackhawk says he never did in the early ’90s: he organized a public demonstration to rally support for the name change.

A few days before, Jirousek and the McGill student union held a poster-making event at the First Peoples’ House.

"I remember I was, in the back of my head, worried that no one would really show up," Jirousek says. "No one cared enough to make a poster."

But slowly, people did show up. At first, it was just the first years on the women’s crew team.

"And more and more people came," Jirousek says. "And it wasn’t just Indigenous people, but it was great to see athletes, my teammates, speaking with some of my Indigenous friends. And see this community really building. Making connections. Making Indigenous students really feel more comfortable, I think. And that was something that I took away as quite powerful."

One student’s sign read “Intent Doesn’t Erase Impact.” Others just read “Change The Name.”

“The common poster we had was just this red backdrop with the words 'Indians,' 'Squaws' and 'Redmen' on the poster," Jirousek says. "And there were lines drawn through the 'Indian' and 'Squaw,' but not through the 'Redmen.' ”

The Demonstration

Then, on the morning of Oct. 31, 2018 demonstrators gathered at one of the main gates on McGill’s campus.

"I remember it being absolutely frigid," Jirousek says. "And I remember panicking, because it was cold. And since it was raining, I needed to secure tents, because we had traditional drummers coming. And then, once the demonstration kind of took off — after I had gotten over all the small hiccups — it kind of just flew by.

"It was exhilarating, really, to see, in the cold, hundreds and hundreds of students had come. Somewhere between 700 and 800 people had come to see it. And it was just so powerful. It was nice looking up into the crowd and seeing so many of my teammates there doing everything they really could to support me."

Twice a year, McGill University holds a referendum period where the student body gets to vote on various issues. Jirousek and some fellow student legislators entered the Redmen name change for consideration this past fall. The results were announced on November 13.

"Eighty percent of the student body had voted yes to changing the name," Jirousek says. "[I was] just relieved to know that students were going to feel OK. This made McGill better. It really did."

McGill’s student referenda aren’t binding. After the vote, McGill formed a renaming council that would decide how to move forward. Its report, released in December, included quotes from Jirousek and other advocates for change.

And it also quoted alumni who opposed the movement. They felt the name was really important to their time at school.

"Non-Indigenous students today are much more educated about what the impact of colonialism has been on Indigenous peoples in Canada," history professor Suzanne Morton says. "I don't think students 25 years ago really understood."

The report describes a Town Hall meeting.

A former varsity athlete said of himself: “I’ve got red in my veins.” Another former varsity athlete compared the team name to a family name, highlighting its role in “emotional attachment, social identity and self-esteem.” A jointly signed submission expressed attachment to the Redmen name so strong that the writers vowed that if the name were changed, they would never again donate to McGill, they would discourage their children from applying to McGill, they would “consider McGill dead to [them],” and might “actively work against its success.”

Working Group on Principles of Commemoration and Renaming Final Report (2018)

"I was at the First Peoples' House, and there were some first-year students who had been reading the report," Jirousek says. "And I just remember seeing them cry. Because here are these people who are trying to support this academic institution. And they stand in opposition to reconciliation to such a degree that they would actively undermine the institution if it chose to take the necessary steps to creating a healthy and welcoming environment to Indigenous students."

The Future Of The Redmen Name

McGill was expected to announce a final decision on the Redmen name by the end of January. But on January 30, the university unexpectedly postponed the decision to the end of the spring term. Suzanne Morton says that with such resounding support from students and faculty on campus, she still thinks a name change is likely to happen — if not now, eventually.

"I think it means that the university understands where we are right now — who is us — and us includes Indigenous students," Morton says. "And it means that there's a future where hopefully more Indigenous students will feel very welcome here."

This segment aired on February 9, 2019.