Advertisement

James Baldwin: America's Prophet, Resurrected

Speaking of the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s, Malcolm X once said to James Baldwin, “I am the warrior of this revolution, and you are the poet.” It turns out that we still need this particular poet half a century later. Baldwin’s words have surfaced in the wake of civil demonstrations following the legal decisions not to indict the police officers responsible for the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Social media have been foregrounding Baldwin’s words in recent months in hopes that he might guide us through the confusion. The lead “Notes and Comment” essay in a recent New Yorker proved that the phenomenon is not limited to social media.

Those encountering [Baldwin's] works for the first time find him not only prophetic, but energizing in a variety of ways.

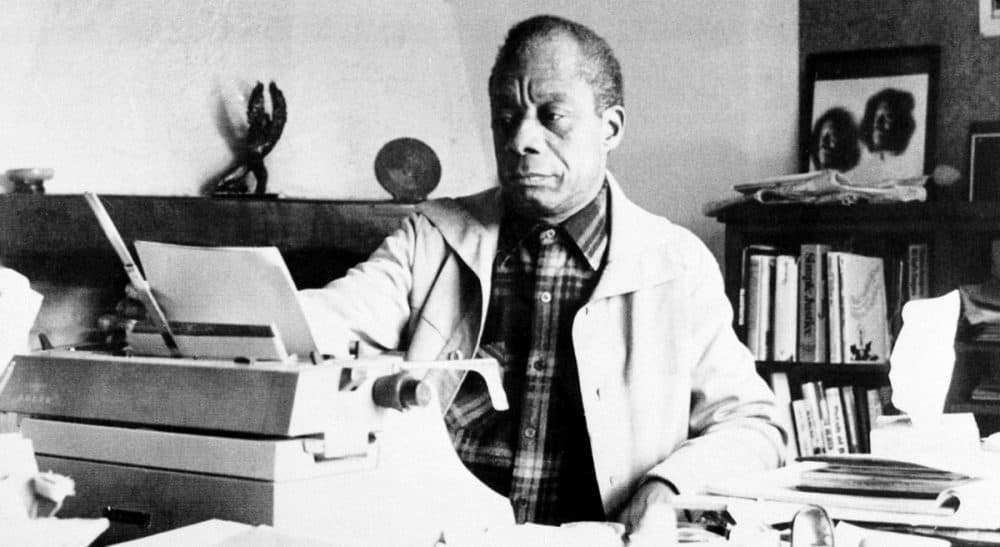

Those of us who study and teach Baldwin do not find this trend surprising. Baldwin was the most prominent African-American writer of the civil rights era, often called a prophet and the spokesman of his race, though he winced at all labels. He was an untrammeled force of nature, a gifted speaker as well as an accomplished, experimental, passionate writer in multiple genres.

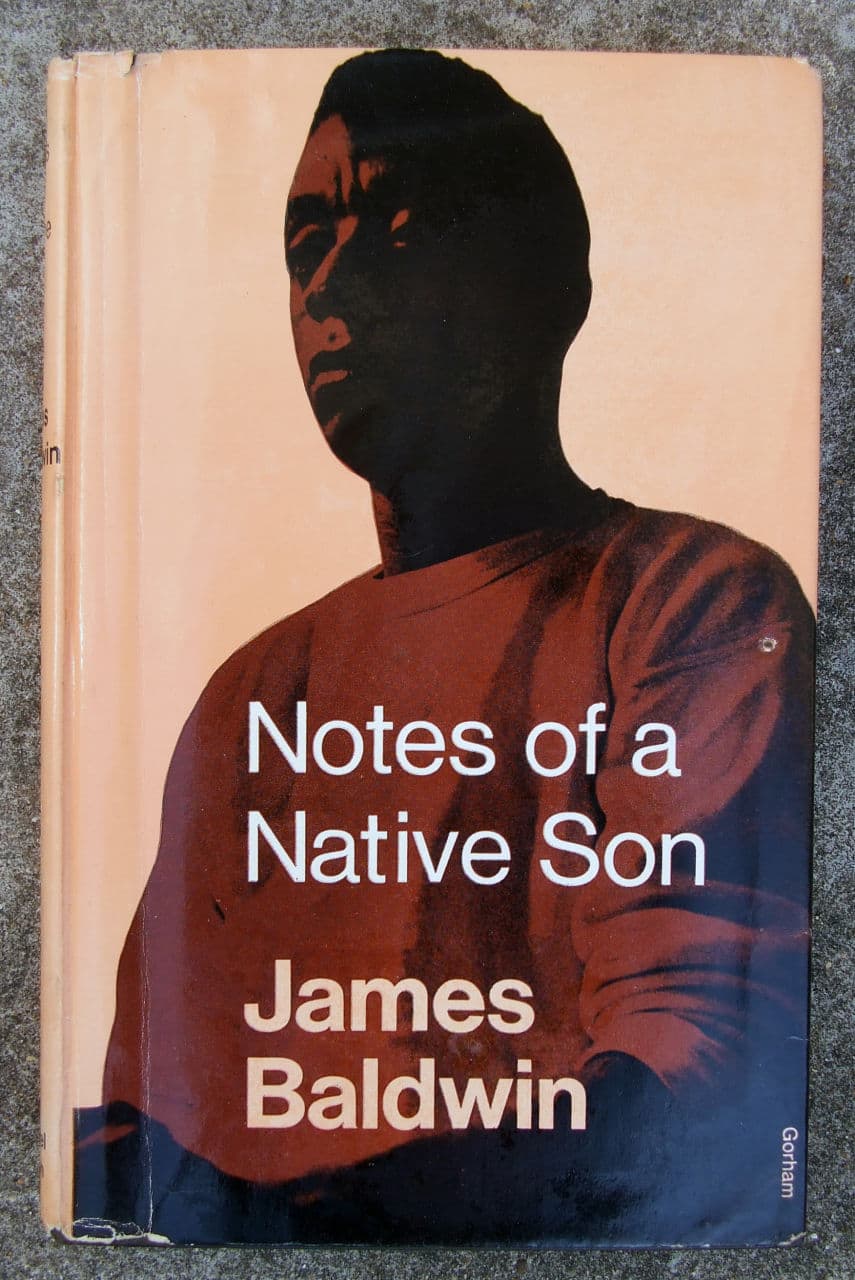

To call Baldwin a prophet has become almost a cliché. Those encountering his works for the first time find him not only prophetic, but energizing in a variety of ways. Reading Baldwin is always an intense, rewarding adventure. This past fall, in my survey of African-American literature, we had just read his essay “Notes of a Native Son” when the Ferguson decision was announced. The confluence of this essay in our class and current events was uncanny. Describing the 1943 Harlem riots, Baldwin writes, “Harlem had needed something to smash. To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need.” Baldwin’s eloquence is startling, and his elegant, passionate phrases are indeed useful captions to the images we have seen recently.

But what is equally valuable in Baldwin’s work is his raw confession, his willingness to be vulnerable and to share his own experience. “Notes of a Native Son” blends the personal with the public so that the reader is directly involved in the writer’s experience. The 1943 Harlem riots happen to have coincided with Baldwin’s father’s funeral, with the birth of his youngest sister and with his 19th birthday. His feelings on that extraordinary day were conflicted, to put it mildly. The essay is partly about Harlem’s need to smash something, but it is largely about Baldwin’s own need to smash something. He recounts a telling incident: In a segregated restaurant, upon hearing “We don’t serve Negroes” for the 100th time, he hurls a water glass at the young waitress who says it, shattering the mirror behind her and nearly getting himself killed by an instant mob. This anger is something that connects him with his father, a man who had descended into bitterness at the end of a lifetime of mistreatment.

It is an essay that examines the consequences of fear, not only the fear of the hostile outside world that turns racial animosity into “a wilderness of smashed plate glass” in Harlem, but the fear of the author’s own capacity for the same type of violence. Baldwin’s most valuable insights combine sermon and confession. He is a font of wisdom, but he tells us unflinchingly about the price he paid for that wisdom: He struggled, and he describes that struggle consistently and honestly, without glossing over his flaws.

Love is at the core of Baldwin’s message. Love, for Baldwin, is essential for the emotional survival of individuals and the very survival of our species.

As he writes in “Notes of a Native Son,” “…hatred itself becomes an exhausting and self-destructive pose. But this does not mean…that love comes easily.” Love is at the core of Baldwin’s message. Love, for Baldwin, is essential for the emotional survival of individuals and the very survival of our species. Love is not a passive or weak endeavor; it requires effort to summon an antidote to hatred, fear, sorrow and suffering, all of which have flooded our screens in recent months.

Confusion and anger make for a volatile mixture, and we need Baldwin, as we always have, to help us sort through the complexity we must face. Yet I hope that Baldwin’s appearance in recent online discussions motivates socially conscious citizens to engage deeply with his work. It is crucial to honor Baldwin’s genius by reading him thoroughly and sensitively. The captions he has provided for recent online images are a gateway into his writing. To really understand Baldwin’s relevance, we must go beyond the snippets that can be contained in 140 characters or fewer. In a world of diminishing attention spans, he deserves our full attention.