Advertisement

What makes the world’s first bar joke funny? No one knows.

Resume

This is the first episode of a two-part series on the origin of jokes and humor. The story appears in podcast feeds under the title, "Jokes, Part I: Sumer Funny, Sumer Not." Listen to part two here.

In the late 1800s, archeologists in Iraq uncovered an ancient clay tablet with a peculiar yet familiar line of text. Scrawled in tiny, wedge-shaped characters was what is arguably the world’s first documented bar joke.

The tablet is 4,000 years old, nearly from the dawn of writing. Roughly translated from the dead language of Sumerian, the joke reads: “A dog walks into a bar and says, ‘I cannot see a thing. I’ll open this one.’”

Get it? Scholars certainly did not. Nor did the thousands of Twitter and Reddit users who responded to a viral post about the joke in March. “It was probably some type of pun based on word pronunciation,” wrote one person. Another guessed that the line was akin to a New Yorker cartoon offering a “vignette of life” in Sumer, the earliest civilization in southern Mesopotamia.

The temptation to decode the joke from a bygone era was palpable — partly because understanding it could reveal something unique about early human civilization.

In this episode, the first of two parts, Endless Thread journeys back in time, attempting to deconstruct the origins of humor and explain an unexplainable joke from the forgotten tablets of the past.

Show notes

- Depths of Wikipedia’s tweet about ‘one of the earliest bar jokes’ (Twitter)

- This bar joke from ancient Sumer has been making rounds (Reddit)

- Sumerian Animal Proverbs and Fables: ‘Collection Five’ (Journal of Cuneiform Studies)

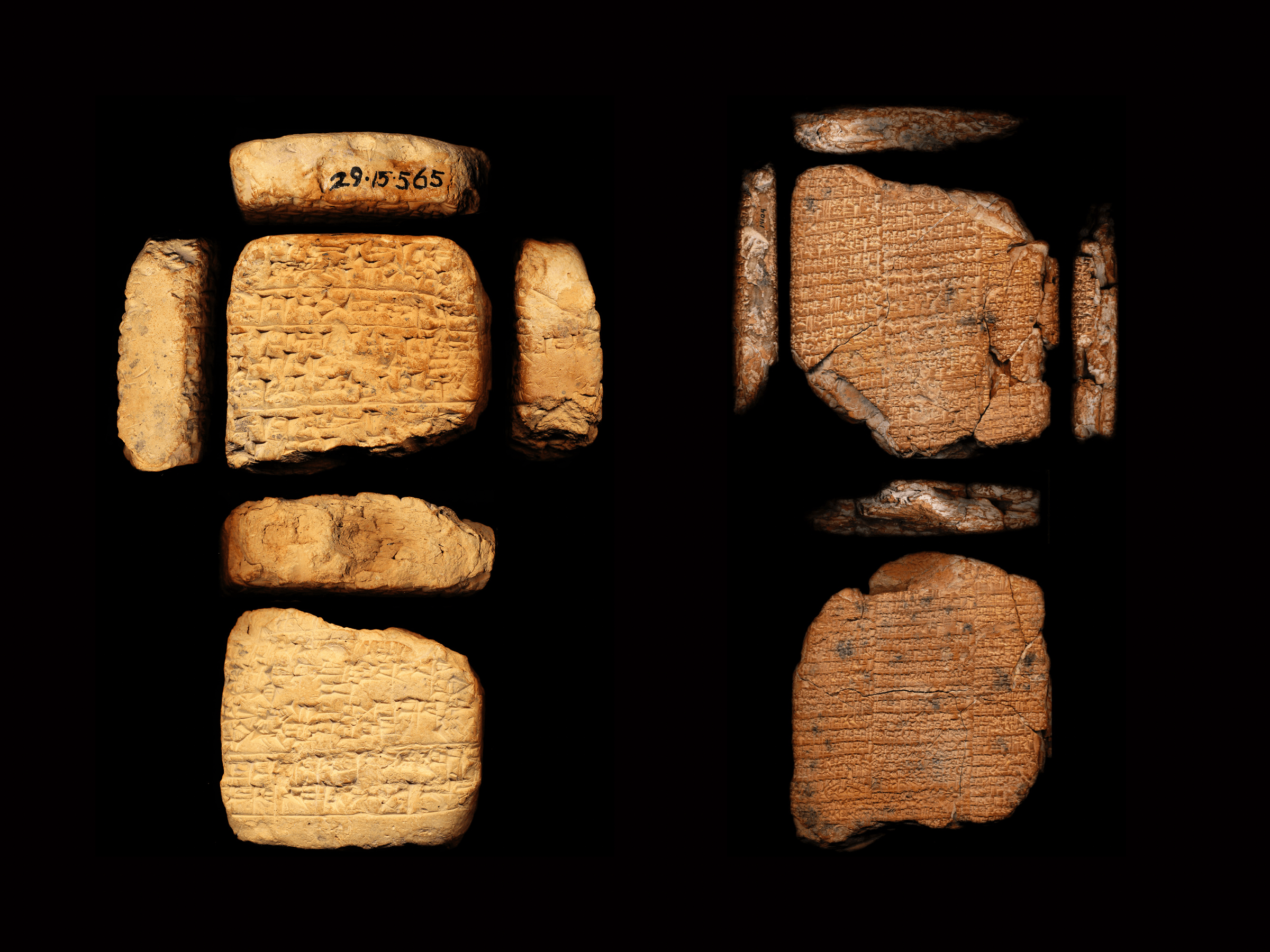

- The two tablets, CBS 14104 and UM 29-15-565, at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, also known as the Penn Museum.

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Ben Brock Johnson: Let’s do the jokes. Let’s make some jokes.

Amory Sivertson: (Laughs.) Knock, knock.

Ben: Who’s there?

Amory: Oh god, I didn’t have anything to say after that.

Ben: A few weeks ago, Amory and I hopped in my car and headed south from Boston. We had jokes on the brain. Sort of.

Ben: You still haven’t finished your joke.

Amory: I know, I’m trying to think of any jokes I actually know, but like…

Amory: In fairness, I was driving. We were on our way to Philadelphia in search of this one particular joke — one that we were told was sitting in a dark storage cabinet, scrawled on an ancient block of clay.

Amory: I’m not really blonde, but I know a blonde joke.

Ben: OK, let’s hear it.

Amory: What do you call a blonde— (Laughs.)

Ben: Apparently, this joke is hilarious. I wouldn’t know.

Amory: It’s just how I am. What do you— (Laughs.)

Ben: This joke we were looking for is not a blonde joke. It’s a bar joke; history’s first recorded “X walks into a bar.” The joke is 4,000 years old — from the infancy of written language. And it serves as a key mile marker in the evolution of humans and, specifically, our humor.

Amory: But there’s one little problem, a mystery that has been bugging scholars for decades since the joke was unearthed. This joke, it is not that funny because nobody gets it — at least, nobody still alive.

(Montage of WBUR staffers and friends.)

Marquis Neal: (Chuckle.) What the f***? (Laughs.)

Dan Mauzy: I don’t get it. I don’t get it.

Saurabh Datar: Maybe I’m too stupid to understand this joke.

Kelvin Brooks: I don’t have an answer nor a laugh for that.

Quiana Scott-Ferguson: I don’t get it. (Laughs.)

Marquis: I got questions, and you don’t have no answers. So you got to figure it out. (Laughs.)

Ben: I’m Ben Brock Johnson.

Amory: I’m Amory Sivertson. (Laughs.) I’m just thinking about jokes.

Ben: We’re coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station.

Amory: Today’s episode: the first of two parts in which we deconstruct the origins of humor. (Laughs.) Oh man, the origins of humor — that’s already funny to me. And we explain an unexplainable joke from the forgotten pages of the past.

Ben: Turns out, apparently, you don’t have to explain the joke for Amory to find it hilarious. You are listening to Endless Thread. “Jokes, Part 1: Sumer Funny, Sumer Not.”

Amory: Our ancient bar joke journey started long before our road trip to Philly, which we’ll get back to, of course.

Ben: For us — and a lot of other people — it started where else?

Seraina Nett: I actually found it on Reddit. On Ask Historians.

Ben: You’re a Redditor?

Seraina: Yes.

Ben: Can you tell me about your Reddit habits?

Seraina: It’s usually more like academic Reddit, I think, than, sort of, generic Reddit.

Amory: Seraina Nett works at Uppsala University in Sweden, where she studies ancient Mesopotamia, including a region called Sumer and its language Sumerian.

She spends a lot of time translating Sumerian, looking for clues about early human development. Most of what she translates, though, is not exactly riveting.

Seraina: Of course, there’s literature and the epic of Gilgamesh and kings telling us about their deeds. But the vast, vast majority of texts that we do deal with are essentially receipts, labor, assignments, payslips.

Ben: Ugh.

Ben: Seraina was one of several thousands of people who happened upon this joke in March on Reddit and initially on Twitter.

Amory: That’s where the account @DepthsOfWiki posted a screenshot from an unlinked, unnamed Wikipedia page. It reads like this: “One of the earliest examples of bar jokes is Sumerian, and it features a dog.”

Ben: So can you read it for us?

Seraina: In Sumerian?

Ben: Yeah. Let’s start there.

Seraina: OK. I’ll do my best. We don’t really know how Sumerian was pronounced, so I’ll do my best approximation.

Ben: Would love that.

Seraina: So in Sumerian it reads: “ur-gir-re ec-dam-ce in-kur-ma / nij na-me igi nu-mu-un-du / ne-en jal taka-en-e-ce.”

Amory: Ba-dum-ksh!

Ben: Trust me, if there were any ancient Sumerians listening to this podcast, they would be rolling on the floor right now.

Amory: No doubt. But to help out you English-speaking listeners, though, we asked Seraina to translate. And, boy, is it a doozy.

Seraina: In English, that means something like, “A dog entered into a tavern and said,” — probably — “‘I cannot see anything. I shall open this,’” or “‘this one.’”

Ben: That’s it. That’s the joke. “A dog walks into a bar,” — or tavern, or something else but more on that later — “and the dog says, ‘I can’t see a thing. I’ll open this one.’”

Amory: If you noticed some hesitation in Seraina’s voice, that’s because scholars have different translations for this joke. Sumerian is the earliest written language on record, with the first examples dating to about 3000 B.C.E. And it’s a dead language.

Ben: Sumerian is also an isolate, meaning it isn’t related to any other known language, making translation an imprecise art. Still, the joke more or less translates as Seraina said. Get it?

Amory: Neither did we. Nor did any of the dozen-plus colleagues and friends we asked over the last couple of months.

(Montage of WBUR staffers and friends.)

Saurabh: Can you say that again? A dog walks into a bar and says?

Ben: I’ll open this one.

Saurabh: So there is no bar, and the dog is the bartender?

Quiana: What can a dog open? They don’t have thumbs.

Marquis: What type of bar is this? What can’t the dog see?

Ben: That’s actually a very astute question.

Tinku Ray: And what’s the answer?

Ben: We’re not sure.

Nora Saks: I’m imagining a dog with a can of Budweiser and, like, using his little paws to open it. And that’s mildly amusing. That’s it.

Quincy Walters: Maybe they had, like, you know, the forethought to know that this cryptic joke would last through the ages and have people on this wild goose chase. And they’re off in, you know, another realm laughing, like the joke is on us, maybe.

Ben: We knew when we started looking into this, we may indeed end up the butt of this joke because we knew we might not find the answer to what makes it funny or what it tells us about the origins of humor. But we were willing to take that chance.

Amory: So a bit of background. A lot of people point to Sumer as the first human civilization. It emerged around 5000 B.C.E. And it was made possible by the Agricultural Revolution. This was before Egypt, Greece, etc. And geographically, it was in Mesopotamia, the region in and around modern-day Iraq.

Gonzalo Rubio: The very name Mesopotamia, the Greek name, refers to the land that is in-between rivers, the Tigris to the east and the Euphrates to the west.

Ben: This is Gonzalo Rubio of Penn State. Another expert we spoke to early on our journey.

He says Mesopotamia is home to a lot of firsts.

Gonzalo: It’s the cradle of bureaucracy. It’s the cradle of agriculture. It’s the cradle of a lot of babies, if you will.

Ben: (Laughs.)

Amory: Gonzalo and Seraina told us that, combined with new large-scale irrigation techniques, the river valleys were so fertile that this agrarian society had an enormous surplus. That made it possible to feed a lot of people — maybe for the first time in humanity.

Ben: We’re talking up to 1.5 million Sumerians, who in turn built some of the earliest cities with culture and taverns and social hierarchy.

Seraina: So you have the elites. Then you have, let’s say, a middle class with craftspeople — for example, merchants, more well-to-do people. And then you have a vast lower class of farm laborers, workers, and so forth. And also enslaved people.

Amory: The humor of the dog-in-a-bar joke was probably related to those Sumerian ways of life, perhaps the middle class or well-off, people with downtime and drinking shekels.

Ben: But while some experts know some things about Sumer, the nuances have been lost, and it’s the nuances that bring jokes to life.

Seraina: I must admit, I don’t understand the punchline. I’m not quite sure what it is.

Ben: OK.

Seraina: It could have been a pun that we don’t understand. It could have been a reference, I don’t know, to a local politician or some famous figure. So it’s very hard for us to tell.

Amory: OK, so this seemed like the first plausible theory. Jokes do often include references to current events and sayings, from “Bye, Felicia!” to “The rent is too damn high!”

Ben: So maybe a local powerful person said, “I’ll open this one,” in some other context and became infamous for it? And this bar joke is actually just comparing him to a dumb dog? Just a guess.

Amory: There are hundreds of guesses online: Maybe the punchline was meant to be physical, unspoken. Or it could be as simple as: “I can’t see a thing because my eyes are closed.” Not a great joke, but maybe that’s all you can expect from proto-humor. Gonzalo had a different thought, though — admittedly, one that felt like it would shut down our investigation before it even began.

Gonzalo: When people say this is a joke, first of all, we don’t even know what it is.

Ben: I mean, it is structured like a joke. There’s a setup (dog goes into a bar, can’t see anything) and a punchline (“I’ll open this one”). But maybe that’s revisionist history. Seraina didn’t even refer to this as a joke when we first started talking.

Seraina: This proverb is in no way special. It’s part of a larger collection of many, many, many proverbs.

Amory: The bar joke — or proverb — is Number 5.77 in a collection of hundreds of other proverbs about dogs, donkeys, husbands. Some read like sayings. Others like weird short stories. But jokes? Depends on how you see things. Like this other proverb Gonzalo told us:

Gonzalo: It’s something like, “Behold! Watch out! Something that has never occurred since time immemorial; the young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.”

Ben: Sorry, I’m going to be really dumb for a second.

Amory: I am too because this is—

Ben: I’m not sure I get the joke. Is the joke that the woman would never admit that she farted in her husband’s lap? Or is the joke that the woman always farts in her husband’s lap? And that’s the joke, that we’re suggesting that it’s never happened before.

Gonzalo: I think the joke is precisely the latter. The joke is that it is expected to happen. To set up the joke by saying, “Watch out, this is something that has never happened, not once.” And then the sentence is, well, “The young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.”

Ben: This fart joke — which, Gonzalo insists, is a joke — this one gave us a little bit of hope. Because it’s structured like the bar proverb. Right? Setup. Punchline. So we thought maybe we’re not rewriting history? This formula has been around.

Amory: And Seraina told us there are more proverbs meant to be funny. The structure’s not always the same, but there is one recurring feature that makes the proverbs stand out as jokes.

Seraina: There’s quite a lot of innuendo — things like sexuality or, I don’t know, excrement. For example, one of my favorite ones is, “A bull with diarrhea leaves a long trail.”

Ben: This is going to be my new after-my-email-signature quote.

Amory: A bull with diarrhea leaves a long trail? (Laughs.) That’s a good way to scare some people from your inbox. Get your email count down.

Ben: (Laughs.) There’s another proverb about the enormity of elephant poop. Another compares the sex appeal of a shepherd to a gardener. One with a longer staff; the other, a nicer bush. Collectively, they struck us as a tad juvenile.

Amory: It also struck us that, on its face, the bar proverb is not that juvenile. “A dog walks into a tavern and says, ‘I can’t see a thing. I’ll open this one.’” No sex. No diarrhea. So maybe it’s not a joke.

Ben: But then Gonzalo told us something interesting.

Gonzalo: The word for tavern, “ec-dam,” for us, it conveys the idea of a pub or a bar. But really, in ancient Mesopotamia, a tavern is also a place where sex trade takes place. So it’s a tavern, but you could also translate it as a brothel.

Ben: “A dog walks into a brothel.” Depending on your perspective, that word change totally alters this joke and also what the dog might be opening.

(Montage of WBUR staffers and friends.)

Saurabh: I don’t think I wanted to say on the record what I think.

Tinku: A door.

Ben: A door?

Tinku: Then maybe he’ll see something or somebody or someone, you know.

Marquis: The dog in the brothel has to be a horny dog. Like, you know the dogs that you go to the house, and he’d just be humping your leg? This got to be one of them dogs.

Nora: Maybe it’s like a sandal. Or a robe.

Ben: Oh, that’s good.

Nora: Yeah, well, I’ll be here all day, guys.

Ben: So, going back to this so-called bar joke, how do you interpret it?

Seraina: It could have been the dog walks into the bar with his eyes closed; “Let me open this,” as in the eyes. Or open, I don’t know, a door. There is also a word that sounds very similar to one of the words that is a word for female genitalia.

Ben: See, you know what? That’s what I was going to ask. That’s where my head was at. Is that right?

Seraina: It’s not a very obvious pun, so I’m not quite sure.

Ben: Right.

Amory: To us, these revelations felt like the thing — the epiphany. Brothels, maybe some genitalia talk. It’s a dirty joke, end of story.

Ben: There’s another complication, though, because it still doesn’t make sense. Or, at least, we’re not laughing. Plus, the translations are too loose and feel kind of unreliable. We mentioned this to Seraina, who dropped one more tantalizing clue about the clay tablet — or tablets that hold our proverb.

Seraina: So this particular proverb is attested on two different versions of the text. And actually, they’re not identical. So, already, somebody screwed up. One of them is also a little bit broken, so it’s hard to tell.

Amory: This thing that everyone’s struggling to understand: No fricken wonder! Because there are two copies. They’re actually both broken, and they don’t match.

(Car ambiance.)

Ben: So we’re blasting down the highway. Amory’s behind the wheel.

Amory: What are we doing next?

Ben: I don’t know, you tell me. What are you doing next?

Amory: Well, I would like to get to our destination, but I don’t know where to go.

Amory: This brings us back to our voyage to Philadelphia, where we’ve arranged to see the primary documents in real life.

Ben: To see these two slabs of clay, which have been in storage for years. To see a joke that may be crumbled or that may be riddled with typos or that may not be a joke at all.

Amory: What we found, in a minute.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Ben: We’re just barely in West Philadelphia.

Amory: Born and raised.

Ben: After a six-hour drive contemplating jokes and primeval humor, we meet our producer Dean at the Penn Museum in Philly.

Amory: Outside, it’s grand — red brick and white marble walls topped with a terracotta roof. Shadowed, though, by a very 90s-looking hospital.

(Door opens.)

Amory: OK.

Dean Russell: OK, so—.

(Door closes.)

Ben: Inside, it’s stuffed with a whole lot of old — and I should say, quite beautiful — stuff.

Amory: “This footprint captures the moment over 4,000 years ago when someone stepped barefoot on a mud brick left to dry in the sun.”

Ben: And they were like, “Ugh, that’s wet.”

Amory: We head to the Mesopotamian artifacts, where we’re meeting a guy who says he’ll show us the goods and maybe bring us closer to figuring this whole thing out. He’s not there when we arrive, so we do a little reading.

Amory: “At first, writing was primarily used to record the movement of goods and uses of labor under the supervision of the temple. Quickly, writing in Mesopotamia could be used to record historical events, dedications to the gods—”

Ben: It’s interesting to read this description and have it be like, we invented writing because people couldn’t remember. People couldn’t stay organized. It was like, “Oh, man. Where did all those clay pots go? Ted, do you remember?”

Amory: Ten minutes later, Dr. Philip Jones arrives ...

Amory: Do you prefer Philip or Phil?

Phil: I generally go by Phil.

Amory: … donning a blue beanie and a laid-back vibe.

Phil: I am the—. What am I? I’m the associate keeper and curator of the Babylonian section.

Amory: Phil walks us to a display case with about a dozen sand-colored tablets ranging from the size of a coaster to the size of a tablet — an iPad. Each one is covered in small impressions made by a stylus.

Phil: If I’m teaching writing on clay, I just use a chopstick. You push the corner in. It creates the sort of distinctive triangular head.

Ben: Some of the scripts can be so tiny and fine that it’s kind of miraculous and also hard to see. Other scripts, just big and sloppy. When we ask about that, Phil tells us something we didn’t know when we first started reporting this story.

Phil: First of all, whenever you see the words “Sumerian literature” or “Sumerian mythology,” you are talking about the texts on these kids’ copies. There are no real adult editions of Sumerian literature.

Amory: So all of the stuff we have is just ancient practice writing?

Phil: Actually, this is not TV, so you can’t see.

Ben: It’s like when Bart Simpson, at the beginning of The Simpsons, is writing the same thing on the chalkboard over and over.

Phil: Yes.

Amory: This feels like a particularly important revelation. Just about every Sumerian tablet ever recovered — including the ones with those juvenile proverbs — they were written by juveniles. All of them, by kids training as scribes.

Ben: Wilder still, these proverbs were class assignments — as in, “Learn your Sumerian well by copying this dirty joke.” This is kind of incredible. Right? Eight-year-old Ben may have been more interested in Latin if he were copying proverbs about turds and brothels.

Amory: (Laughs.)

Ben: As enlightening as these display tablets are, though, we came looking for our proverb. And it’s time to dig it out.

Phil: (Door opens.) This is the tablet room.

Amory: Oh, wow. Floor to ceiling, practically, of very skinny file cabinets.

Ben: Whoa, you just pulled out a drawer that was full of tablets. What? This is amazing.

Phil: So this is the—. This is where they live.

Amory: This tablet room is closed to the public. It’s obvious why. The entire thing is like this epic library organized by what Phil calls a “higglety-pigglety” Dewey Decimal-like System.

Ben: I pull on more random drawers, making the communications person who is with us very nervous.

Amory: You might make it even more higglety-pigglety, Ben.

Ben: She’s worried about more higglety-pigglety.

Amory: Does every single skinny drawer of this file cabinet contain tablets?

Phil: Yes.

Amory: Every single one?

Ben: Why don’t you find out?

Communications director: No, no.

Amory: (Laughs.)

Ben: Each one of these things is a couple inches deep and several feet wide. And the tablets inside, they smell like history — dating back to 2900 B.C.E. Many were damaged by time, pieces of fictions that needed to be reassembled.

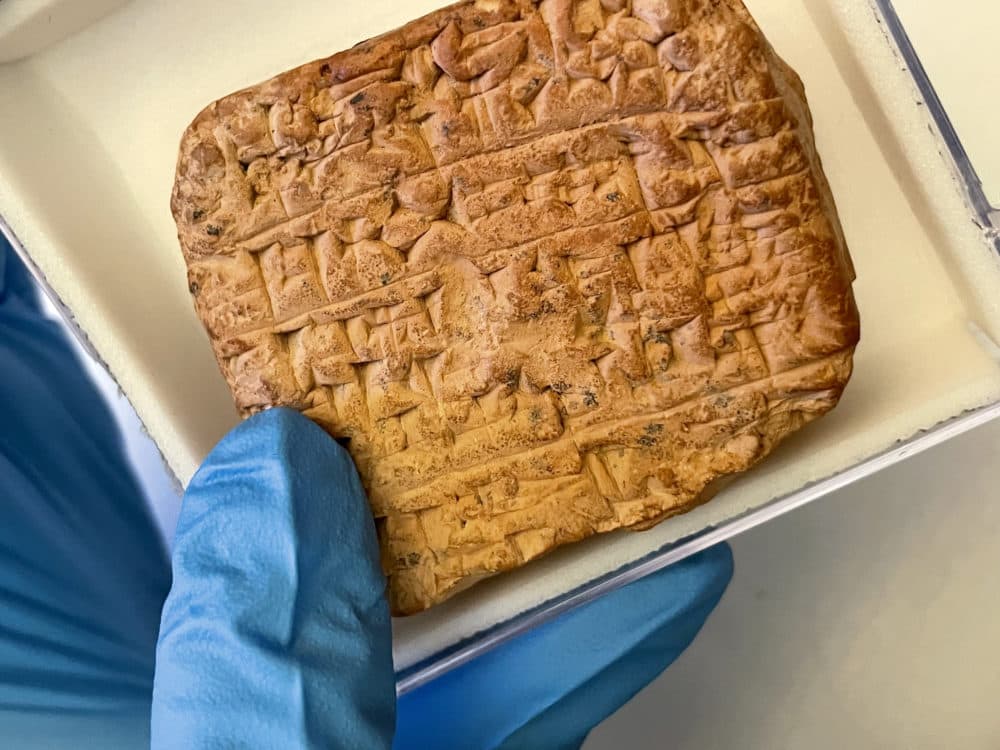

Amory: Phil lets us poke around a little bit, pretending we’re Indiana Jones, and then he corrals us to a long table. He puts on blue latex gloves and reaches for the lid of a shallow box.

Phil: I think our proverb, the dog proverb, is here. Well, “the dog proverb,” it’s a whole bunch of proverbs about dogs.

Ben and Amory: (Laughs.)

Phil: So the dog-in-the-tavern is here, and I think it’s somewhere around here.

Amory: This red clay tablet is the size of about two postcards. It’s speckled black and misshapen, edges fragmented, fault lines through its center. Phil’s blue finger shifts through the markings, covering every square centimeter.

Ben: It’s extremely exciting for us to look at this piece of clay together. Exciting enough that I feel like again I’m making the communications person for the museum very nervous.

Amory: (Laughs.)

Ben: So, eventually, Phil halts at the words we’ve been seeking. The text is so tiny and cramped that it seems like it would be utterly illegible. But it’s so cool.

Amory: The proverb is that small in this language?

Phil: Yes. Yes.

Amory: Phil has two tablets with the bar proverb. The larger one, he says, was probably for practice. The other — the one we’re gawking at — may have been an exam. Despite what Seraina said, Phil says they’re not that different, which is a little disappointing to hear.

Phil: So it’s, doo doo doo doo doo. So the “ur-gir-re”—. So an “ur” is basically a quadruped with nasty teeth. So it can be a dog or a big cat.

Ben: These two ancient tablets, he tells us, were etched around 1700 B.C.E. At first, this means nothing to us, really, but Phil explains. By that time, Sumer had actually been overtaken by the Babylonian empire. The culture was pretty similar, except that the Sumerian language had already died out.

Amory: Kids at the time spoke Babylonian, also called Akkadian. Only scribes continued to learn Sumerian. It was considered more dignified — kind of like learning Latin today. Knowing this, it seems now even more likely to us that there are mistakes in the text. For instance:

Phil: This is interesting because that really is an Akkadian word.

Amory: Whoops.

Ben: Ignoring the random non-Sumerian word, the dog enters the taverny brothel or brothely tavern. He can’t see a thing. He opens this one. Only, Phil says the word “open” is very similar to the word for “close.”

Phil: I mean, not in this case. I think it obviously means to—. Well? It obviously means to open in this case because they do spell—

Amory: Are you sure?

Ben: Yeah, you sound unsure.

Phil: I think I’m fairly sure because normally, if they mean “to close,” they’ve ended up using a different spelling than this one.

Amory: Phil assures us: Don’t worry about it too much. Slippery Sumerian translation is an inescapable fact — not just in this proverb. You kind of just jigsaw around until the true meaning comes together.

Ben: But we have more questions. Namely, is this a joke? Maybe even one that helps us understand, I don’t know, the origins of humor?

Ben: Are you—? So you’re team “Not Joke.” Or are you team “Joke”?

Phil: I’m team “Humorous Sayings.” So maybe we’re talking Seinfeld rather than Bob Hope.

Ben: OK. I like it.

Amory: Joke? Sure. Check. What’s it mean? Again, we ask Phil.

Ben: Now, as far as we know, Phil is not a Redditor. But he spent some time on the thread when we sent it to him, going through the various theories. Some, he says, are more plausible than others.

Amory: But he adds that everyone’s missing some very important context about the dog.

Phil: The dog is a specific character type. It’s a guard dog whose job is to keep the wolves from the sheep. And in the proverbs, you know, it’s operating on the basis that it’s a personality type that is fairly brutal and not really to be messed with.

Ben: Interesting. That puts like a whole ‘nother layer on this thing because I feel like I wasn’t making any assumptions about the dog other than its general doggyness.

Phil: I was trying to think of cartoon examples. He’s more like the dog in the Tom and Jerry cartoons and not Scooby Doo.

Amory: I was going to say, I think I’ve been picturing more of a Scooby Doo than—

Phil: Yeah. No.

Amory: So a guard dog. Gritty. Tough. With a job to do. What’s the dog open?

Ben: A lot of people online assume that the “this one” the dog opens is a door into a room where people are physically preoccupied. Phil, though, thinks that doesn’t mesh with the way other proverbs use the word “this.”

Finally, we get what we think is a solid explanation.

Phil: I think usually in proverbs, when they say “this,” it refers to something you’ve already heard in the proverb, not to something new. So I think the idea that he’s opening rooms and revealing, you know, couples in flagrante doesn’t quite go with how I would see the word “this” functioning. So I did wonder whether this is more the idea that letting the guard in negates his use because, basically, he wants to see out, he’s going to open the door, and so everybody else outside the tavern can now see in. I mean, I think that’s a legitimate way of looking at it.

Ben: Phil covers the old clay. We wistfully shuffle out. And, at this moment, we buy his theory. A brothel’s guard dog is sitting outside the door under the bright Sumerian sun. He’s scaring away unwelcome Peeping Toms. But then he leaves his post.

Amory: He goes inside, and his eyes aren’t used to the dark, so he can’t see anything. He opens the front door again, propping it to let in a little light. Now, outside, all those Toms are looking in, seeing their politicians and neighbors in flagrante, as Phil said. The guard dog messed up. Get it?

Ben: We think so? Are we laughing? Mmm, that’s a lot of explanation for a joke.

Amory: But even if we buy Phil’s theory — which, given what we know about the typos and the child writers and the words that could mean X or Y, maybe we shouldn’t buy it — but if we buy his theory, that still leaves the question: Why does any of this matter? Why do so many scholars, Redditors, Twitterers, Tweeters — why do we all care about figuring this joke out?

Ben: As we’re leaving, our producer, Dean, poses one more question.

Dean: Why do you think humor is so important in a lot of these proverbs?

Phil: Well, I think generally, you know, proverbs or this kind of proverbial saying has a degree of humor which is universal across human cultures.

Amory: Humor. Human humor. Two enormous questions about early human development are: (1) How did humor come about? What are its origins? And (2) Why do we even tell jokes? Why did we write them down in clay and stone and on paper and online?

These proverbs — this bar joke — they are the first documented examples of humor. Understanding them, scholars think, can help us understand this critical feature that is literally everywhere in our lives.

Ben: And understanding that may reveal something unique about how we all came to be, how humans evolved. That is all in this joke. No joke. So our journey through the past to the origins of humor has to continue.

And in the next episode, we will travel even further back, millennia before the age of writing, before Sumer, before humans.

Amory: That’s coming up in Part II.

[CREDITS]

Amory: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Want early tickets to events, swag, bonus content? My blonde jokes? Pics of Ben’s drinking-shekel collection? Join our email list! You’ll find it at wbur.org/endlessthread.

This episode was written and produced by Dean Russell. And it’s hosted by us, Amory Sivertson and Ben Brock Johnson. Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski.

Our web producer is Kristin Torres. The rest of our team is Nora Saks, Quincy Walters, Grace Tatter, and Megan Cattel.

Also, major thanks to all of our friends and colleagues who gave us their best guesses at this old joke. Kelvin Brooks, Saurabh Datar, Victor Hernandez, Dan Mauzy, Frannie Monahan, Marquis Neal, Tinku Ray, Nora Saks, Quiana Scott-Ferguson, and Quincy Walters.

Endless Thread is a show about the blurred lines between digital communities and a spouse’s fart, held in from time immemorial. If you’ve got an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or a wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up. Email Endless Thread at WBUR dot ORG.

See ya next episode for more jokes.